Precision farming: greater accuracy in agriculture

The method behind it is as old as plant breeding itself: Phenotyping delivers answers to questions such as whether new varieties cope well with the environmental conditions at a location. Or whether and where they are infested by pests.

“Throughout KWS’ more than 160-year history, its experts have assessed plants in the field,” says Bauer. “That’s vital in developing new varieties.” Breeders sow new plants every year and then evaluate how they develop in the field. They record the plants’ size, color, growth rate, the number and shape of their leaves, and other features. In many small, often very laborious steps, breeders can thus ultimately supply varieties tailored perfectly to the farmer’s needs.

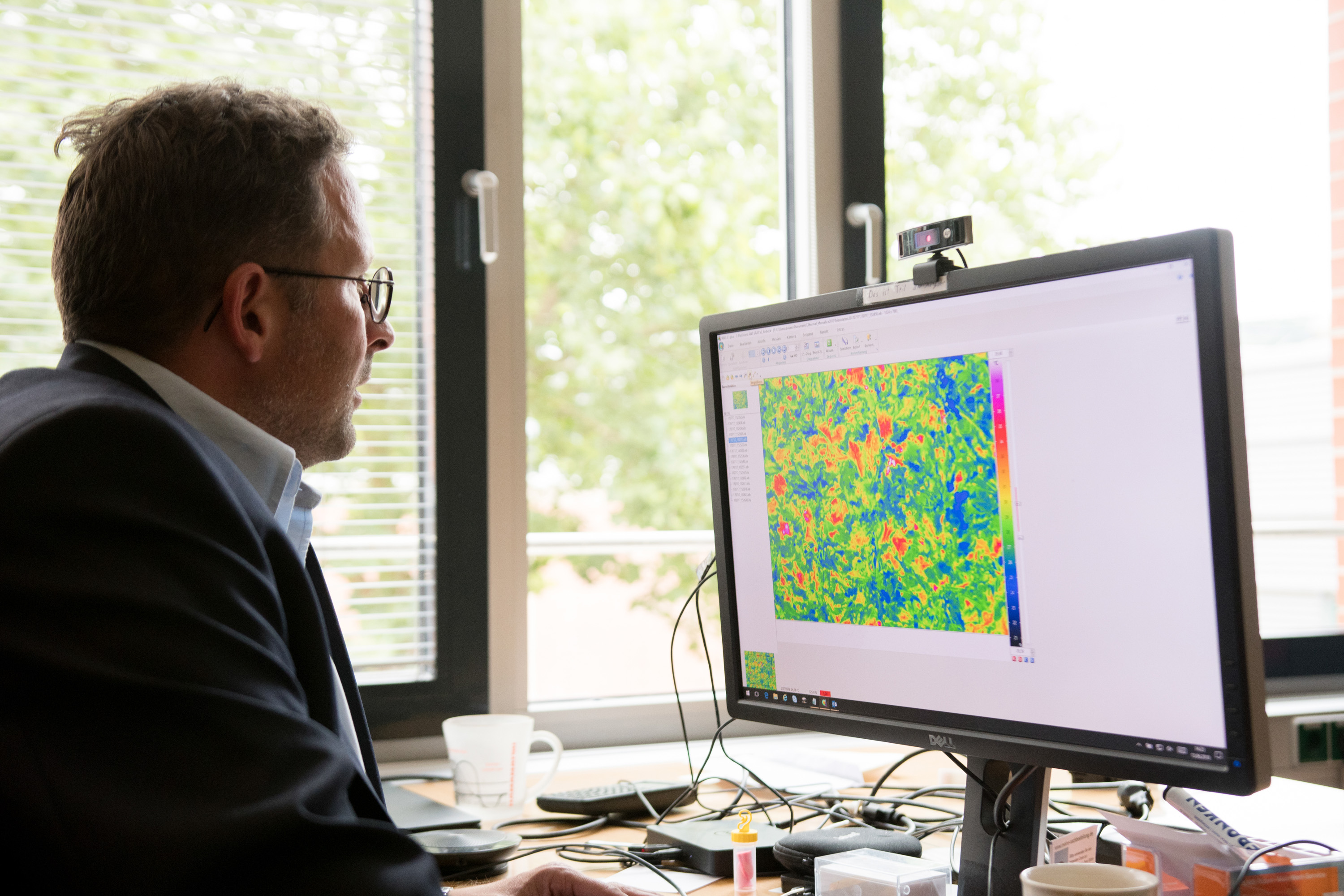

The aerial photos and software analysis speed up that process significantly. And they have more advantages for farmers as well, explains the technology expert Bauer. Fungal infestation, dry areas, low chlorophyll content: Nothing goes undetected by the digital sensors. And because the measurement devices and software never get tired, the results of analysis of the plants’ rate of growth and the number and size of their leaves are often more precise and available faster than without technical assistance.

As Bauer puts it bluntly: The human eye is not accurate enough. “If several people walk through a field to assess development of the foliage, you get results that are usually very similar, but that nevertheless have slight differences.”

Technology is always objective and helps rule out those differences – and also has the advantage of speed: “No human can assess such huge areas with such unerring objectivity.”