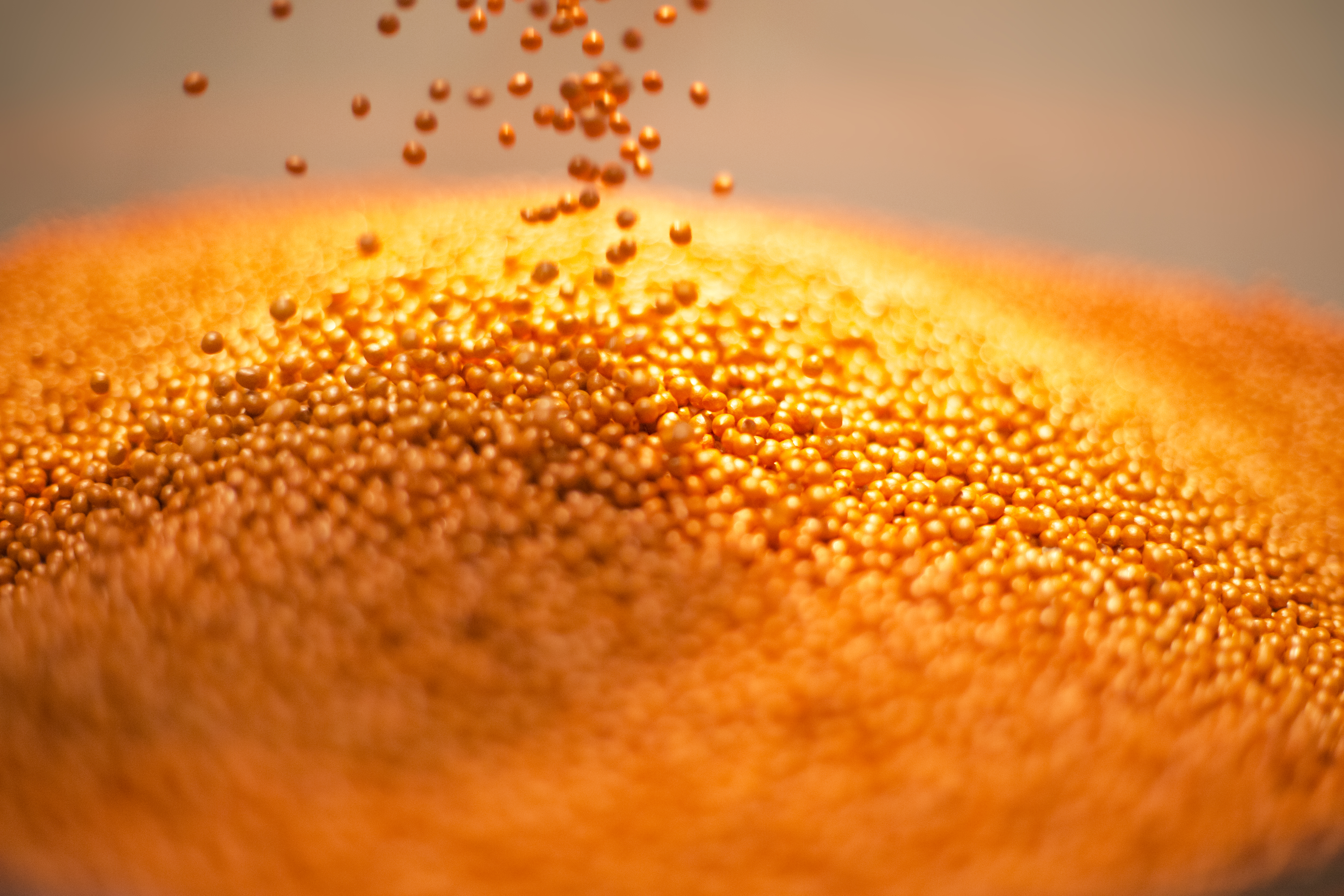

High tech for maximum quality: checking seed in the computed tomography scanner

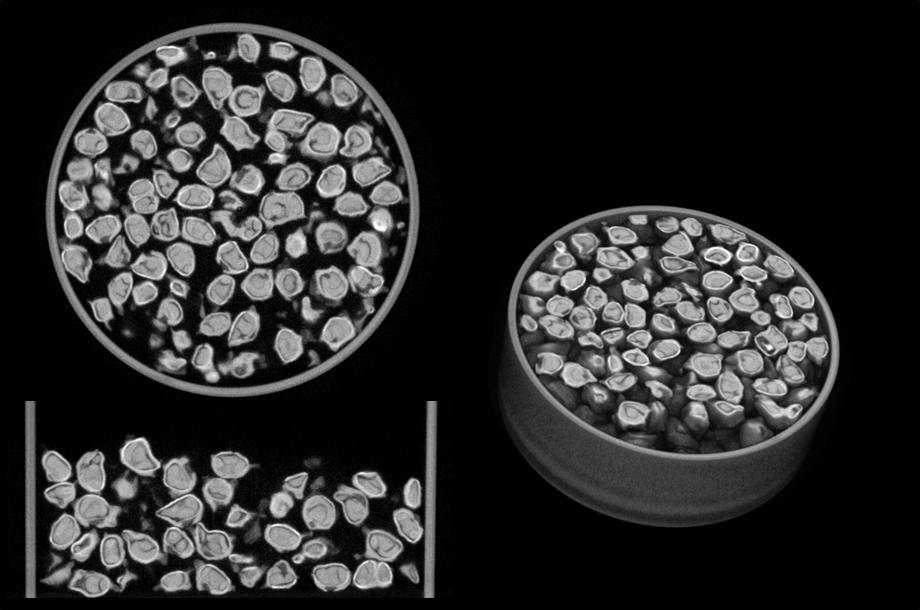

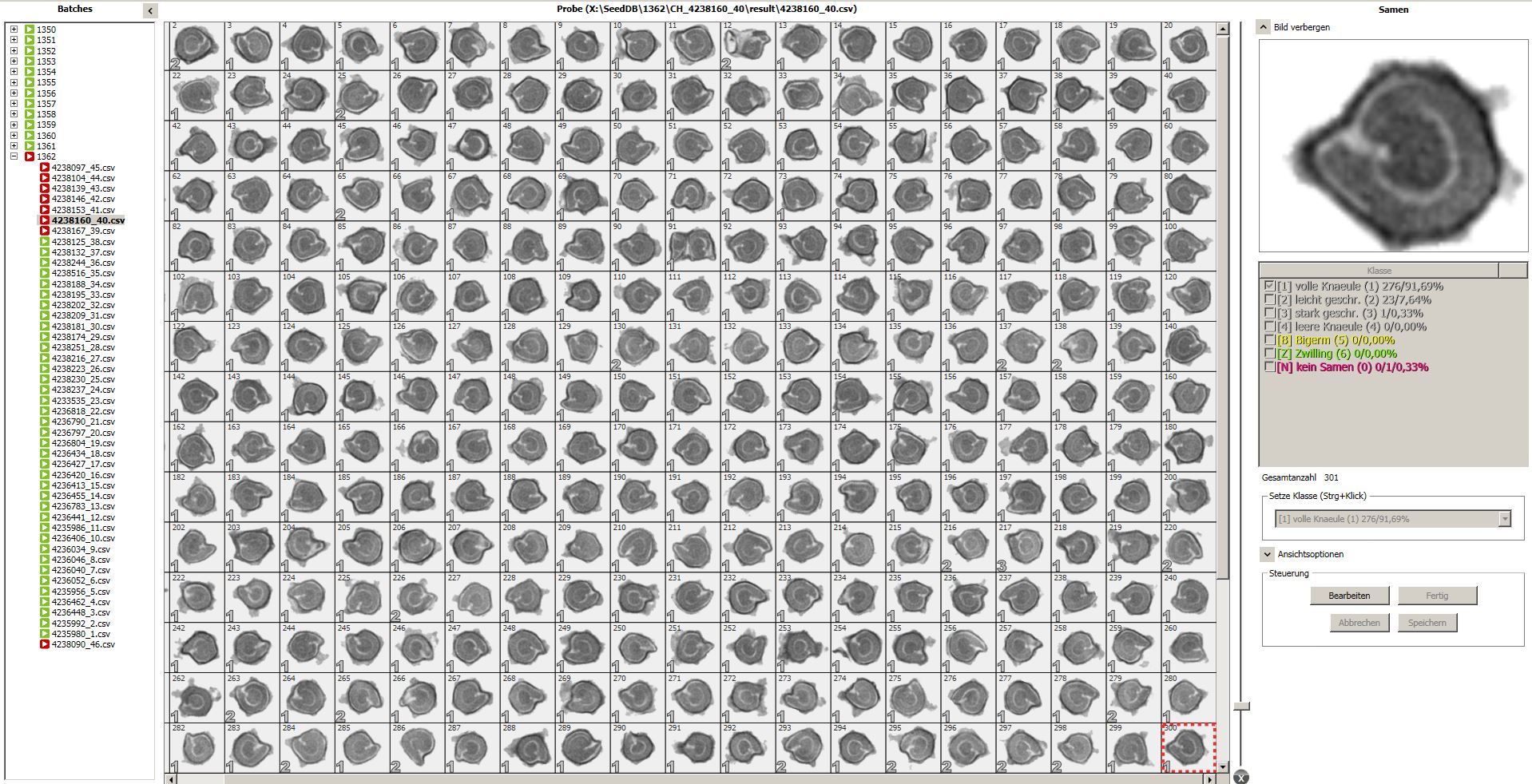

Top-quality seed is the key to achieving the very best yields. One of the central requirements for seed to produce high-yielding plants is for it to contain a healthy embryo. But experts can’t tell that from the outside of a seed. An ideal solution would be if they were able to look directly inside the sugarbeet seeds, which are just a few millimeters in size. And KWS’ seed experts enable such an examination with a 3D computed tomography scanner.

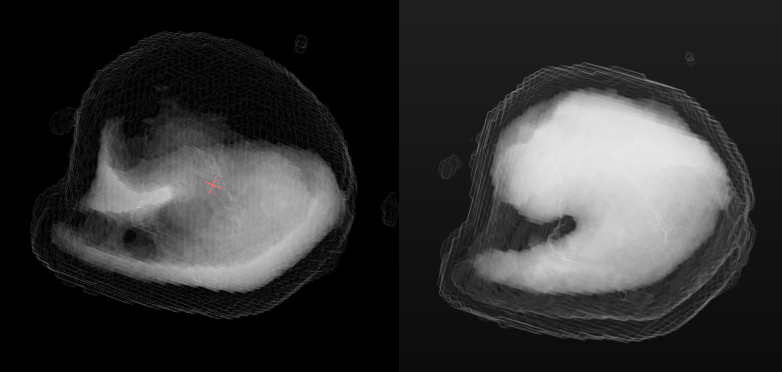

The computer has pieced together an animation of the examined seed from numerous images

Discover more

Your contact